When learning to read musical notation, the representation of pitch is pretty logical. When the blobs go up, the pitch gets higher, when the blobs go down the pitch gets lower. So far, so good.

However, what’s less clear is rhythm. Most musical theory works start with the crotchet, or quarter note, and then work outwards. In reality, starting with a crotchet is a little bit like learning the alphabet by starting with the letter M, or learning to count starting at 5!

So let’s go back to where our modern notation came from.

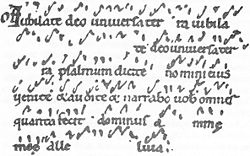

Unsurprisingly, like the notation in this picture, it started out being blobs and lines going up and down. This was all very well for someone who already basically knew the songs, like a monk who sung the same psalms over and over again. Not so great, though, if you’re trying to learn a new song from what’s been written down without having heard it.

As a result, a system of representing rhythm developed. At first, this was by joining groups of blobs together with bars. The direction and number of blobs joined told singers which rhythm the notes were supposed to be sung to.

The blobs became the basic count and were called “breves” because they were short (or brief) compared to the “longa” or long note. The breve was a black blob, and the longa was a black rectangle with a little tail. It’s not exactly clear why they used those, but so it was.

As music got more complicated, singers needed new divisions of notes. To show a semibreve, the breve was drawn as a diamond. Then to make it shorter and create a minima (tiny note), an upwards line was added. Then a little tail on the top.

Somewhere around the 15th century, scribes added in an extra level by beginning to draw the longer notes as open shapes, and filling in shorter ones with black centres. This allowed another level of notes, open with a stick, and closed with a stick, before the adding a tail.

The shape of the heads slowly became less important, thanks to the use of tails and the open/closed distinction. As music writing ceased to be the exclusive realm of trained monastic scribes, they became round, like the notes we know today.

So, if you’re trying learn your way around note values, remember the breve (which we rarely use today is the basic block. Chop a breve in half, and you get a semibreve. Chop a semibreve in half and you get a minim (remember – minimal, tiny note!). Chop that in half and you get a “fusa” which is now known as a crotchet. Half of that is a semifusa, now called a quaver.

Finally, it’s worth remembering all this if only to totally confuse anyone who uses American terms. After all, it’s really the breve that’s the “whole note” and semibreves are “half notes”, half notes or minims are really “quarter notes” and so on…!

Want to know more about how to read music? Discover Singing offers theory lessons in Leith, Edinburgh.

0 Comments